Photo courtesy of USHMM

I had the distinct pleasure of meeting Holocaust survivor Gabriele Silten through the Remember_The_Holocaust group moderated by Fred Kahn. She immediately sent me copies of her written work (see titles list below), including her autobiography Between Two Worlds. She also agreed to an online interview which we conducted by e-mail just this week. Below is the substance of that interview.

Q: Was writing your autobiography therapeutic? Is that why you decided to write it?

A: No, it was not therapeutic. I decided to write it because a lot of people–friends– pushed me to do so and I thought it was a good idea. I had to relive that whole time, which at least meant that it all came to the surface and I could then deal with it.

Q: You talk about your family being assimilated and not practicing Judaism. Was your family not very religious?

A: Obviously not. Assimilated means just that; that they were NOT religious, did not keep the dietary laws, did not go to temple, did not keep the holidays, etc. We practiced nothing at all.

Q: Did they observe the High Holy Days? Can you summarize your views about religion, faith and God as a young child?

A: No, as stated above, they observed nothing at all. As a young child I had no views about God, religion, faith or anything like it. So there is nothing to summarize. I came to all this much, much later.

Q: As to the “Jewish star,” you mention that it had to be firmly adhered to all clothing. Where did your family buy the printed, yellow fabric?

A: As I found out much later, after the war and when I was in my 40’s, we, in my family, bought the stars at one of the local temples. There were several places like that, depending on where you lived. They didn’t cost much but they had to be BOUGHT and a rationing coupon for material was necessary, as well.

Q: Were the stars sewn to every piece of clothing? If so, how long did that take your mother and grandmother to complete?

A: Yes, to every piece of outer clothing – not onto underwear. But if you wore a blouse and a sweater, for example, then it had to be on both pieces of clothing. I have no idea how long it took my mother and grandmother to do that. I do remember that my mother put the stars into a solution of vinegar and water. They were not color-proof and if you didn’t do that, the yellow would bleed onto the material of your dress, shirt or something like that. So they needed to be soaked like that first and after that they were all right.

Q: When you discovered that your friend Peg and her family had been taken away, what did you think had happened to them?

A: I didn’t know for sure, of course, but thought that either they had been “taken away” as we called it, i.e. arrested, or that they had gone into hiding. I didn’t know much about hiding, but had heard of it.

Q: How old were you before you realized what the Nazis were doing to Jews in the East?

A: I had no idea whatsoever what the Germans were doing to the Jews in the East. Not even most adults knew that. All we knew, and especially we children, was that we never got card or letter and never heard from any of them again. So we figured it must be very bad indeed. Most of us heard the word “Auschwitz” after the war for the first time. I, as a person, did not find out until one day I looked for something to read in my parents’ book case (I was allowed to do that) and found a hidden book about what I now know as Auschwitz. There were many photos and I figured out in no time that this was what had happened to the Jews who were transported out of Westerbork and Theresienstadt where I had been. It was obvious that they could not possibly have survived. I was at home alone that day and I was 15 years old.

Q: Your paternal grandparents must have known what awaited them at Auschwitz. How did they know it would be better to die by their own hands than to face the horrors of Auschwitz?

A: I don’t know whether they or my maternal grandmother actually KNEW what awaited them at Auschwitz. According to my father, they figured that they were too old to go through all of that, too old to “work” (they were told about work camps, after all), too old to “relocate.” My paternal grandfather was a pharmacist and gave poison to my maternal grandmother, to his own wife and to my father’s family, i.e. my parents and me. My paternal grandmother used it when her name appeared on the list for the next transport from Westerbork; she was there with us.

Q: If it is not too painful, can you talk more about your Omi’s death in Westerbork, July 1943, and how it affected you?

With her Omi Marta in 1935

A: It is not painful, since I have long ago accepted it and think, in fact, that she and my other grandparents were heroes for doing this. I don’t know that I would have had the courage, or would have the courage today, in fact. I know that my father told me at the time that Omi was ill and had to go to the “hospital”–yes, there was one in Westerbork. Then, the next day, he told me that she had died. He did not then tell me that she had committed suicide. That came out many years after the war, when I must have been about 16 or 17 years old. Affected: I missed her a lot, especially at first. She was the one, when she lived with us, to help me with multiplication tables, sewed clothes for my doll, taught me how to braid hair. I missed all of that. But the, Westerbork was such a bad place that children grew up overnight and I became more independent and played less if at all.

Q: In your book, you said that it took approximately eight days to make the 80-mile trip by train to Westerbork and only two days from there to Theresienstadt. Why do you think the train to Westerbork took so long? Were you given any water or food inside the cattle car?

A: No, I didn’t say that at all. I said that we were “picked up” (arrested) early in the morning – about 9:00 am and that we had to wait around in various places till about noon. We arrived in Westerbork at about 11:00 pm which is 12 (twelve) hours. Today, by train, car or bus, it takes 2 hours, traffic permitting. We were not given any water or food in the cattle car to Westerbork, nor immediately after arrival. It did take two (2) days to Theresienstadt; we left on January 18, 1943 and arrived on January 20, 1943. I don’t remember whether we were given either food or water on that trip. I doubt it, though. As for the 12 hours to Westerbork, the train was probably shunted onto side rails when another train or troop train had to pass. That was the Germans’ usual procedure.

(Editor’s note: I missed a typo in the question, above, when I e-mailed it to Ms. Silten. Page 78 of Gabriele’s book Between Two Worlds says “it was a journey of at least eight hours,” not eight days. My apologies.)

Q: At the two camps, many of your friends were deported further East. Did you have any idea what that meant?

A: No, I didn’t. Even though I was a child, we children overheard the conversations between adults, if only because it was so overcrowded that you had no distance from one another. The adults didn’t know either; none of us had heard the name Auschwitz, not till much later. We didn’t know about extermination camps, gas chambers or anything of the kind. All I knew was that my friends were gone; had disappeared and that we never heard from them again, no cards, no letters. Just emptiness.

Q: Do you think that your father’s occupation as a pharmacist had any bearing on how you were treated at the camps?

Gabriele at age 5

A: Yes, I do, but didn’t learn that until a year or so ago. It appears that a friend and business friend of my grandfather’s convinced the Germans that my father was an inventor who was in the process of inventing a spray or something like that which would help wounded soldiers in the field. Then this same guy sent my father various instruments, etc. (like Bunsen burners) to Theresienstadt and my father was able to convince the Germans that he was really working very hard on this. It was all a fairy tale, my father was no inventor and had no plans for such a spray or whatever. But we stayed in Theresienstadt instead of being transported to Auschwitz which we certainly would not have survived.

Q: After the war, did you suffer at all from “survivor’s guilt” once you knew how many had perished (more than 80 percent of Holland’s Jewish population, according to Robert S. Wistrich)?

A: No, I didn’t and don’t now. Directly after the war, every adult, incl. my parents told me – and the other surviving children – to forget about all of that, not to think about it, we needed to go back to school; our job was to do well there and to think of the future. They also told us that, since we were “only” children, we couldn’t possibly have suffered, we couldn’t possibly remember anything and especially not correctly, that we, basically, had not know anything out of the ordinary had happened. We all know better now, but then that was the idea. I had no idea how many children or Jews in general had been murdered (I NEVER use the word “perish”. One “perishes” from a disease; one “dies” of disease or old age, etc. and if one is “lost”, then one can be found. One loses one’s keys, etc. but not people, not in those circumstances. In the camps and other places, Jews were murdered. So that is the word I use. Words are important to me and I like to use the correct one when possible. In this case that is the word “murdered”). I did not know any numbers until I was in my twenties or thirties and started doing some research for myself.

Q: Before the war, it seems that you were a very inquisitive little girl, but by war’s end, you had learned not to ask too many questions. What questions did you have for your parents after your safe return to Holland?

A: None! I wasn’t supposed to ask questions so I didn’t. On the few occasions when I did dare to ask anything, I’d get a very vague answer. Like – question: where are the X family? Answer: Oh well, they, ehhh. they didn’t come back. Which was jargon, for they had been murdered. Jargon, incidentally, which survivors still use today. We still use the same phrase. Eventually, actually very soon, I stopped asking questions and started trying to find out things for myself – about when I was 16 or so.

Q: In your ID picture taken after you returned to Amsterdam in 1945 you have a decent amount of hair. Did you ever have your head shaved due to lice?

A: No, I didn’t ever have my head shaved, though I saw plenty of people – both men and women – who did. The men would just walk around with their shaven head (as they do now, and guess what THAT reminds me of????) but the women wore a headscarf over their shaven heads. One knew anyway why they did, but it just looked better that way. In fact, I never had lice in camp; my mother made sure that I stayed clean or at least as clean as one could stay. I did have lice, ironically, before deportation, in2nd grade because my friends and I exchanged caps. So we all ended up with the lice that one of us had!

Q: In the months leading up to your liberation from Theresienstadt, it seemed that you had lost hope. Is there one thing to which you can attribute your survival?

A: Not really. I had lost hope, especially after my friend Hans had been deported. I didn’t think that the war or the camp, etc. would ever end; it would just go on and on. I don’t know what made me go on; all I can tell you is that I had then and have now a very good imagination. So basically what I did all throughout those years was change things around in my mind: the real reality became fantasy – unreal. It didn’t exist. My fantasy, my imagination became reality; in my mind I could go where I wanted, I could fly from the attic of the barracks to outside Theresienstadt; I could be anywhere. Maybe that helped, I don’t know. I can’t put my finger on what really kept me alive, either at the beginning or towards the end.

Q: Did you or your family ever return to Germany?

A: My parents did a couple of times for a visit to a museum or some such thing. My father also went twice to the Frankfurt Fair which was a business fair, probably something to do with pharmaceuticals since he was a pharmacist. I HAD to go for reparation business in (I think) 1995 and HATED it. All I could see was Nazis marching and swastika flags flying and I heard boots on cobble stones. I knew that it wasn’t real, it was in my mind but I couldn’t get out of there fast enough! It was absolutely horrible and I swore I would never go back and indeed I haven’t gone back and won’t. My father wanted – as I learned much later – in my thirties – to return to Germany to live, but my mother put her foot down and said NO !!!!!, UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES. We stayed in Holland.

Q: How did the experience of the Holocaust affect your outlook on life?

A: Probably 100 %. I do not trust people easily if at all, I am suspicious by nature, I feel at home only with other survivors. It has made me want to do better than other people (this also goes for other Child Survivors and probably adults as well). I didn’t want children if I had married (which I didn’t) because I find this not a world into which to produce a child. On the other side, as I said earlier, I was brought up in an assimilated way, but in 1984 or 1985 came to a belief system. I was looking for “something” and it never even occurred to me to look outside of Judaism. I was introduced to the local Hillel rabbi who turned out to be a son of survivors. He talked to me and I went to see him every week for an hour even though he was, of course, there for the students at the colleges and not necessarily for the community, in any case not as a counselor. But he took me on all the same, answered my questions, gave me books to read and invited me to the Hillel Friday night services. There have been several rabbis since then at Hillel and I stayed with Hillel for a long time. Meanwhile I also became member of a temple – locally – . Now there is a new rabbi at Hillel and I have outgrown Hillel, I think, after about 20 years. I go to temple regularly and love it. I love the traditions, the music and everything that goes with temple going.

Q: Aside from what you’ve already covered in the book and these interview questions, is there anything you’d like to share for my blog audience?

A: Yes, I think so. In my opinion the only way to avoid genocides and other holocausts is to accept people the way they are. People talk about “tolerance” but I don’t like that word because it makes me feel that I am saying: “I don’t like you but I won’t say anything.” What I mean is that I accept people exactly the way they are, odds and quirks and all. One can try discussion and talks, and one can try to change people’s minds, but one doesn’t always succeed. Prejudice comes from ignorance, from not knowing what the other is about. So to get rid of prejudice one needs education, one needs to be taught that “other” is not “bad” just “different.” I try to live my life that way and hope I am succeeding. I’d like to add that most of our Child Survivors are in the “helping professions,” i.e. teachers, social workers, lawyers, doctors, etc., in a MUCH higher percentage than the “regular” population. Interesting, isn’t it?

A: Yes, I think so. In my opinion the only way to avoid genocides and other holocausts is to accept people the way they are. People talk about “tolerance” but I don’t like that word because it makes me feel that I am saying: “I don’t like you but I won’t say anything.” What I mean is that I accept people exactly the way they are, odds and quirks and all. One can try discussion and talks, and one can try to change people’s minds, but one doesn’t always succeed. Prejudice comes from ignorance, from not knowing what the other is about. So to get rid of prejudice one needs education, one needs to be taught that “other” is not “bad” just “different.” I try to live my life that way and hope I am succeeding. I’d like to add that most of our Child Survivors are in the “helping professions,” i.e. teachers, social workers, lawyers, doctors, etc., in a MUCH higher percentage than the “regular” population. Interesting, isn’t it?

###

Titles by R. Gabriele S. Silten:

Between Two Worlds: Autobiography of a Child Survivor of the Holocaust, Fithian Press, Santa Barbara, 1999, ISBN 1564741265

Is The War Over?: Postwar Years of a Child Survivor of the Holocaust, Fithian Press, McKinleyville, Calif., 2004, ISBN 1564744299

The Past Is Never Far Away: Unpublished Prose and Poetry from the Years 1979 to 2006, ©2007 R. Gabriele S. Silten

High Tower Crumbling: poems by R. Gabriele S. Silten, Fithian Press, Santa Barbara, 1991, ISBN 0931832861 (out of print)

Dark Shadows, Bright Life: poems by R. Gabriele S. Silten, Fithian Press, Santa Barbara, 1998, ISBN 1564742539

Related Links:

Ruth Gabriele Silten on USHMM site

Gabriele on Children of the Holocaust site

Her testimony on Westerbork

When you think of the “hidden children of the Holocaust,” the images those words conjure are probably Jewish kids on a freedom-bound train or hidden in a small space in someone’s attic. Rachel Sarai was a very German-looking Jewish child hidden in plain sight of the “stupid Krauts,” as she calls them. But while this 7-year-old girl was certainly a heroine, she was not a child, for Rachel lost her childhood at a very early age.

When you think of the “hidden children of the Holocaust,” the images those words conjure are probably Jewish kids on a freedom-bound train or hidden in a small space in someone’s attic. Rachel Sarai was a very German-looking Jewish child hidden in plain sight of the “stupid Krauts,” as she calls them. But while this 7-year-old girl was certainly a heroine, she was not a child, for Rachel lost her childhood at a very early age.

Dachau was the genesis point for the much feared Death’s Head Units, the Totenkopfverbande-SS. It was ground zero for the Holocaust. Eicke’s model camp became the blueprint for all future camps, including the killing centers in Poland. From September 1939 – February 1940, the Death’s Head Units, which became part of the armed, or Waffen-SS, were trained at Dachau while prisoners were temporarily housed at Mathausen.

Dachau was the genesis point for the much feared Death’s Head Units, the Totenkopfverbande-SS. It was ground zero for the Holocaust. Eicke’s model camp became the blueprint for all future camps, including the killing centers in Poland. From September 1939 – February 1940, the Death’s Head Units, which became part of the armed, or Waffen-SS, were trained at Dachau while prisoners were temporarily housed at Mathausen. “In early 1937, the SS, using prisoner labor, initiated construction of a large complex of buildings on the grounds of the original camp. Prisoners were forced to do this work, starting with the destruction of the old munitions factory, under terrible conditions. The construction was officially completed in mid-August 1938 and the camp remained essentially unchanged until 1945. Dachau thus remained in operation for the entire period of the Third Reich.”

“In early 1937, the SS, using prisoner labor, initiated construction of a large complex of buildings on the grounds of the original camp. Prisoners were forced to do this work, starting with the destruction of the old munitions factory, under terrible conditions. The construction was officially completed in mid-August 1938 and the camp remained essentially unchanged until 1945. Dachau thus remained in operation for the entire period of the Third Reich.” Though there was a large gas chamber built for the purpose of extermination, most sources say that it was never used to kill prisoners. However, one website contends that, at a minimum, prisoners were used as guinea pigs to test gassing methods here (See

Though there was a large gas chamber built for the purpose of extermination, most sources say that it was never used to kill prisoners. However, one website contends that, at a minimum, prisoners were used as guinea pigs to test gassing methods here (See

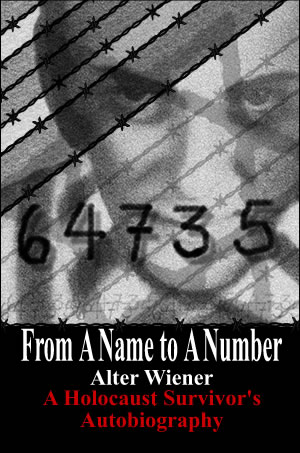

He moved to Oregon in 2000 and began working on his memoirs between public appearances and speaking engagements, many in local schools. Alter Wiener’s autobiography

He moved to Oregon in 2000 and began working on his memoirs between public appearances and speaking engagements, many in local schools. Alter Wiener’s autobiography